On the autumn day of 2022, the Lev Tolstoy Memorial House in Khamovniki was closed for restoration. The wooden building (21 Lva Tolstogo St.) was dilapidated, communications were worn out, and the supply and exhaust ventilation system, which was so necessary to maintain optimal temperature and humidity conditions in the museum, needed to be replaced.

The staff carefully packed and dusted the exhibits. However, it was decided not to hide the main ones from the eyes of visitors during the restoration (Architectural and Construction Technologies company, STORK). They were included in the expositions of other museum sites. For example, an office went to the Prechistenka branch: a chair, the legs of which Leo Tolstoy slightly sawed off due to myopia, a leather armchair and a famous desk with balusters, behind which the novel "Resurrection" was written, as well as about a hundred other works.

We have prepared a project for scientific restoration, which was scheduled to be completed by the fall of 2025. But everything turned out differently: the house where the writer spent 19 winters opened its doors to visitors earlier — on January 3 of this year.

Vladimir Ilyich Tolstoy, who left the post of Adviser to the President of the Russian Federation on cultural issues, took over the post of Director General of the L. N. Tolstoy State Museum last summer. He was able to accelerate the restoration, "successive processes were carried out in parallel."

The Khamovnichesky House, an object of cultural heritage of federal significance, was built in 1805 under Prince Ivan Meshchersky. During the War of 1812, it did not burn down in the Napoleonic conflagration. Fortunately for the house, the French lived in it.

When Count Tolstoy decided to purchase housing in Moscow, as it was time for his eldest children to get an education and his daughters to go out, Major General Adam Vasilyevich Olsufiev advised the count to become his neighbor: "From there you can constantly go for a walk to Vorobyovy Gory, never setting foot on the pavement, crossing from your a garden in our garden."

In 1874, the mansion in Dolgokhamovnicheskiy Lane, number 318 of the Khamovnicheskaya section of the 1st precinct, ended up in the hands of collegiate secretary Ivan Alexandrovich Arnautov. In 1882, he sold the Khamovnichesky house with outbuildings and a hectare of land to Count Tolstoy. Demonstrating the quality of the structure, Arnautov tore off a couple of planks of the cladding. Striking the logs of the log house with a ringing axe, he praised them, saying that the logs were "ossified."

Khamovniki, inhabited by weavers in the 12th century, was a working-class suburb surrounded by gardens and vegetable gardens at the end of the 19th century. Factories were bustling all around—Giraud's silk products, the perfumery. "I live among factories. Every morning at 5 o'clock, one whistle is heard, another, third, tenth, and on and on," Tolstoy reported.

A brick wall separated the brewery (in Soviet times, the All-Russian Research Institute of Soft Drinks was located here) and the estate, which also included an outbuilding, a kitchen, a gatehouse, a gazebo and a carriage house. There was no electricity, running water or sewerage. But the house was surrounded by a magnificent garden in its natural neglect with mounds in the southern part and an elegant pattern of paths.

As a close relative of the Tolstoys wrote, "there are more roses than in the gardens of Hafiz; there are an abundance of strawberries and gooseberries. There will be ten apple trees, 30 cherries, 2 plums, a lot of raspberry bushes and even a few barberries. The water is right there, almost better than Mytishchi. And the air, and the silence. And this is in the midst of the capital's pandemonium." It was because of the garden that Tolstoy, who disliked Moscow, acquired urban real estate.

On October 8, 1882, the family moved to the estate. Against the background of the boorish walls, Tolstoy was experiencing a deep spiritual and ideological crisis. In the 1880s, he decided to clean up, reduce his needs to peasant life, stopped eating meat and "did not feel the slightest deprivation." The writer's wife, Sofya Andreevna, did not share his vegetarian urges, but nevertheless monitored the calorie intake.

The house book, one of the museum's exhibits, says that the family dined on prentanier soup, rice and salmon pie, and the count ate separately "mashed potatoes, two eggs and a baked apple." The dining room in the house is distinguished by its emphasized simplicity. Tolstoy's place at the walnut table, set for a six o'clock lunch, is marked by a glass

Under Arnautov, the mansion was one-story, which was not enough for the large Tolstoy family. Then the ceilings were raised and the second floor was built. There was a large reception hall with a Becker piano and a grand staircase in two flights. The younger children mastered it like a slide and had fun sliding down the steps on large trays.

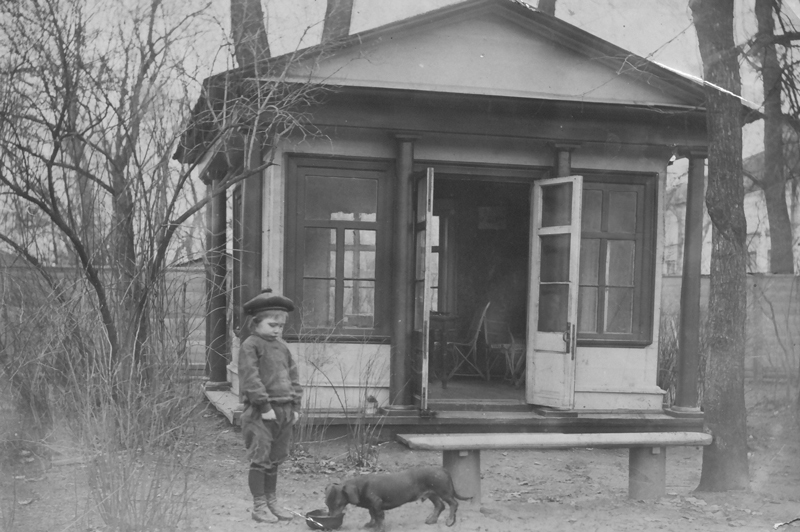

After the reconstruction, to which architect Mikhail Illarionovich Nikiforov was involved, the house had 16 rooms. Long corridors divided the first and second floors in two. In the parent's bedroom today, you can see a Tunisian crocheted bedspread, fashionable in the 19th century, owned by Sofya Andreevna, who always aspired to comfort. At night, by candlelight, she browsed through the drafts of her husband's novels at the mahogany bureau. Above the entrance to the nursery, the hooks from the swings on which the children swung have been preserved. In the nursery are the belongings of Vanechka, the last, thirteenth Tolstoy child, who did not live to be seven years old and died of scarlet fever in February 1895. A doll, a cage for a finch, a rocking horse, snow skates, French recipes, a beaded napkin, the story "The Rescued Dachshund", which Vanya dictated to his mother.

T he Italian window looks out onto the garden. The busiest place was the playground in front of the house. Croquet was played here in the warmer months, and the ice rink was flooded in winter. Even Leo Nikolaevich Tolstoy enjoyed skating. A children's slide was being built near the wing. They drank tea in the summer in a small gazebo. Sofya Andreevna brought 70 young oaks and maples from Yasnaya Polyana and planted them in the Moscow garden. Unfortunately, they didn't.

L iving in Khamovniki, Tolstoy got up at 5-6 o'clock in the morning and performed all the points of his routine. The day was divided into four parts — four "teams". They alternated between all human abilities — physical labor, mental, handicraft and communication with people. The count cleaned his room, cleaned his clothes, chopped wood, heated the stoves, pumped water from the well. At the age of 67, he mastered cycling and shoemaking.

In 1911, after her husband's death, Sofya Andreevna sold the Khamovnichesky house to the Moscow City Council.The hostess carefully packed all the things, some were transported to Stupin's warehouse on Sofiyskaya Embankment, some to Yasnaya Polyana, having previously compiled an inventory. Thanks to this inventory, the exposition of the Leo Tolstoy Museum was formed, which opened in Khamovniki on November 20, 1921.

During the two years of the current restoration, the foundations of the estate have been strengthened, rotten structural elements have been replaced, bricks and wood have been cleaned to preserve the authenticity of the walls as much as possible, and the facade paints have been stripped of layers. Tiled stoves, old parquet, and ceiling cornices have been restored in the main house. The wallpaper has been recreated using old samples. And, of course, the old temperature and humidity control system has been replaced with a new one.

The staff carefully packed and dusted the exhibits. However, it was decided not to hide the main ones from the eyes of visitors during the restoration (Architectural and Construction Technologies company, STORK). They were included in the expositions of other museum sites. For example, an office went to the Prechistenka branch: a chair, the legs of which Leo Tolstoy slightly sawed off due to myopia, a leather armchair and a famous desk with balusters, behind which the novel "Resurrection" was written, as well as about a hundred other works.

We have prepared a project for scientific restoration, which was scheduled to be completed by the fall of 2025. But everything turned out differently: the house where the writer spent 19 winters opened its doors to visitors earlier — on January 3 of this year.

Vladimir Ilyich Tolstoy, who left the post of Adviser to the President of the Russian Federation on cultural issues, took over the post of Director General of the L. N. Tolstoy State Museum last summer. He was able to accelerate the restoration, "successive processes were carried out in parallel."

The Khamovnichesky House, an object of cultural heritage of federal significance, was built in 1805 under Prince Ivan Meshchersky. During the War of 1812, it did not burn down in the Napoleonic conflagration. Fortunately for the house, the French lived in it.

When Count Tolstoy decided to purchase housing in Moscow, as it was time for his eldest children to get an education and his daughters to go out, Major General Adam Vasilyevich Olsufiev advised the count to become his neighbor: "From there you can constantly go for a walk to Vorobyovy Gory, never setting foot on the pavement, crossing from your a garden in our garden."

In 1874, the mansion in Dolgokhamovnicheskiy Lane, number 318 of the Khamovnicheskaya section of the 1st precinct, ended up in the hands of collegiate secretary Ivan Alexandrovich Arnautov. In 1882, he sold the Khamovnichesky house with outbuildings and a hectare of land to Count Tolstoy. Demonstrating the quality of the structure, Arnautov tore off a couple of planks of the cladding. Striking the logs of the log house with a ringing axe, he praised them, saying that the logs were "ossified."

Khamovniki, inhabited by weavers in the 12th century, was a working-class suburb surrounded by gardens and vegetable gardens at the end of the 19th century. Factories were bustling all around—Giraud's silk products, the perfumery. "I live among factories. Every morning at 5 o'clock, one whistle is heard, another, third, tenth, and on and on," Tolstoy reported.

A brick wall separated the brewery (in Soviet times, the All-Russian Research Institute of Soft Drinks was located here) and the estate, which also included an outbuilding, a kitchen, a gatehouse, a gazebo and a carriage house. There was no electricity, running water or sewerage. But the house was surrounded by a magnificent garden in its natural neglect with mounds in the southern part and an elegant pattern of paths.

As a close relative of the Tolstoys wrote, "there are more roses than in the gardens of Hafiz; there are an abundance of strawberries and gooseberries. There will be ten apple trees, 30 cherries, 2 plums, a lot of raspberry bushes and even a few barberries. The water is right there, almost better than Mytishchi. And the air, and the silence. And this is in the midst of the capital's pandemonium." It was because of the garden that Tolstoy, who disliked Moscow, acquired urban real estate.

On October 8, 1882, the family moved to the estate. Against the background of the boorish walls, Tolstoy was experiencing a deep spiritual and ideological crisis. In the 1880s, he decided to clean up, reduce his needs to peasant life, stopped eating meat and "did not feel the slightest deprivation." The writer's wife, Sofya Andreevna, did not share his vegetarian urges, but nevertheless monitored the calorie intake.

The house book, one of the museum's exhibits, says that the family dined on prentanier soup, rice and salmon pie, and the count ate separately "mashed potatoes, two eggs and a baked apple." The dining room in the house is distinguished by its emphasized simplicity. Tolstoy's place at the walnut table, set for a six o'clock lunch, is marked by a glass

Under Arnautov, the mansion was one-story, which was not enough for the large Tolstoy family. Then the ceilings were raised and the second floor was built. There was a large reception hall with a Becker piano and a grand staircase in two flights. The younger children mastered it like a slide and had fun sliding down the steps on large trays.

After the reconstruction, to which architect Mikhail Illarionovich Nikiforov was involved, the house had 16 rooms. Long corridors divided the first and second floors in two. In the parent's bedroom today, you can see a Tunisian crocheted bedspread, fashionable in the 19th century, owned by Sofya Andreevna, who always aspired to comfort. At night, by candlelight, she browsed through the drafts of her husband's novels at the mahogany bureau. Above the entrance to the nursery, the hooks from the swings on which the children swung have been preserved. In the nursery are the belongings of Vanechka, the last, thirteenth Tolstoy child, who did not live to be seven years old and died of scarlet fever in February 1895. A doll, a cage for a finch, a rocking horse, snow skates, French recipes, a beaded napkin, the story "The Rescued Dachshund", which Vanya dictated to his mother.

T he Italian window looks out onto the garden. The busiest place was the playground in front of the house. Croquet was played here in the warmer months, and the ice rink was flooded in winter. Even Leo Nikolaevich Tolstoy enjoyed skating. A children's slide was being built near the wing. They drank tea in the summer in a small gazebo. Sofya Andreevna brought 70 young oaks and maples from Yasnaya Polyana and planted them in the Moscow garden. Unfortunately, they didn't.

L iving in Khamovniki, Tolstoy got up at 5-6 o'clock in the morning and performed all the points of his routine. The day was divided into four parts — four "teams". They alternated between all human abilities — physical labor, mental, handicraft and communication with people. The count cleaned his room, cleaned his clothes, chopped wood, heated the stoves, pumped water from the well. At the age of 67, he mastered cycling and shoemaking.

In 1911, after her husband's death, Sofya Andreevna sold the Khamovnichesky house to the Moscow City Council.The hostess carefully packed all the things, some were transported to Stupin's warehouse on Sofiyskaya Embankment, some to Yasnaya Polyana, having previously compiled an inventory. Thanks to this inventory, the exposition of the Leo Tolstoy Museum was formed, which opened in Khamovniki on November 20, 1921.

During the two years of the current restoration, the foundations of the estate have been strengthened, rotten structural elements have been replaced, bricks and wood have been cleaned to preserve the authenticity of the walls as much as possible, and the facade paints have been stripped of layers. Tiled stoves, old parquet, and ceiling cornices have been restored in the main house. The wallpaper has been recreated using old samples. And, of course, the old temperature and humidity control system has been replaced with a new one.